In 2001, Science Museum curator, [the late] Dr. John Griffiths, stated: “The Wood press is the last hot-metal press to survive the break-up of Fleet Street and it represents the end of an era that spanned 500 years. Its preservation, in perpetuity, as part of the National Collections of Science and Technology, ensures its iconic status. We are proud to be involved in such an important acquisition”.

At the time of the Northcliffe House project in 1999, I was Managing Director Consultancy at AOC South and won the commission to advise about the archaeological and heritage aspects of a redevelopment project from the Hilstone Corporation. The part played by AOC Archaeology in making possible the preservation and transfer of the Wood printing press to the Science Museum was not widely reported [eg a BBC News report ~

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/1665086.stm]. This is a story that I have meant to tell for the last 20 years [this year is the 20th anniversary of the event], had not ‘the highways and byways of life’ got in the way.

Northcliffe House was opened in 1927 and was built to replace the nearby Carmelite House (1897-1899), which was no longer sufficient for Associated Newspaper’s requirements: it was designed by Ellis and Clarke, who were to become the leading specialist newspaper building architects in London. Northcliffe House represented a significant development, one of the first of a new generation of this building, View of Northcliffe House in 1944 not only in its size and scale, but also in the way it was designed to combine the different components of the newspaper production process as efficiently as possible within the building type.

This first stage in our project was to undertake a Desk-based Assessment of the Henry Wood’s newspaper printing press located in a basement of Northcliffe House, Tudor Street, London, EC4. The assessment was carried out as part of a planning application for the conversion of Northcliffe House to offices and a restaurant. Northcliffe House was formerly the printing and publishing building of the Daily Mail and Evening News, part of the Associated Newspapers group. The building had stood empty, and the press inactive, since printing ceased in the late 1980s.

Northcliffe House was listed Grade II in 1988 and was located within the Whitefriars Conservation Area. In 1991, consent was granted for a scheme, involving retention of the street facade only and the demolition of the complete structure within the building. As part of the consent for development, a planning condition was placed upon the surviving Woods printing press, erected in 1934, to ensure its retention.

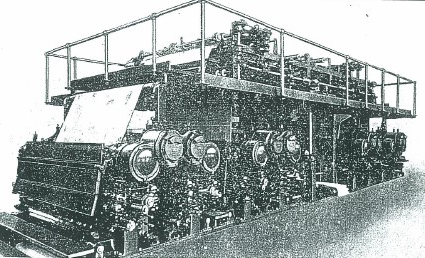

The majority of the surviving press was almost certainly manufactured by the Wood Newspaper Machinery Corporation. This is indicated by the name ‘Wood’ cast or rolled onto the north side of the folder frame and the similarity of the surviving printing units to those manufactured by the Wood Corporation which is illustrated in contemporary publications (Isaacs 1931; Associated Newspapers 1924-1926 ~ see below).

The Wood Corporation were an American firm, based in New York. They took their name from Henry A Wise Wood, who appears to have been both the owner and the person responsible for the designs patented by the firm. The Wood Corporation took out a number of patents relating to newspaper machinery during the 1920s. Their principal patent related to improvements in the inking and paper feed mechanisms of the printing units (United States Patent Specifications no.1327580). Wood’s improvements received fulsome praise in contemporary trade journals; his press installed in the new offices of the Philadelphia Inquirer between 1925 was described as:

‘(the) new wonder of the newspaper world …. (an) almost human machine, which signalizes (sic) a great revolution in fast and economical newspaper production.’

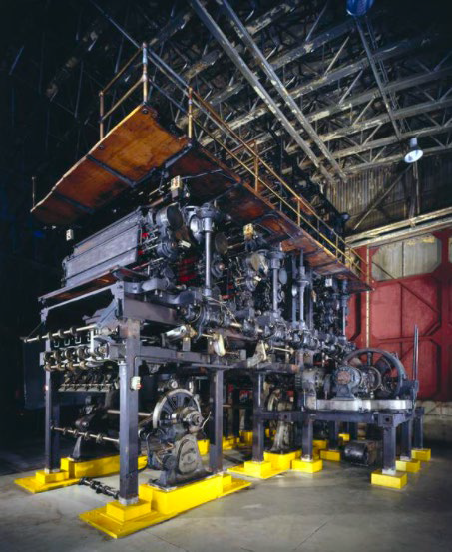

The press was capable of producing 576,000 copies per hour of a newspaper of up to 12 pages and could be arranged to produce 72,000 copies per hour of a 96 pages paper, with many permutations in between. The press consisted of 12 units, was 160 feet long, and driven by four 250 h.p. motors.

An excellent archaeological Desk-based Assessment report –

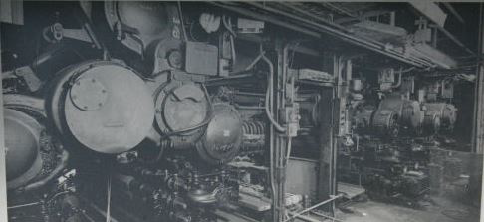

https://www.academia.edu/6928960/Printing_Press_Northcliffe_House_Tudor Street_City_of_London_EC4_Industrial_Archaeology_Report_1999 – was carried out by my colleague Shaun Richardson in difficult circumstances and is the basis for the technical details in this article. The surviving machinery formed approximately one-third of the original length of the press line; its overall dimensions were approx. 8.50m in length, approx. 3.6m in width and a towering approx. 8.3m in height and it weighed approx. 140 tonnes. It was divided into three levels; the lower level rested directly on the basement floor, whilst the middle and upper levels were supported by a steel frame incorporating a walkway around them. AOC had to organise the installation of temporary lighting which made photography rather difficult, requiring long exposures. The freelance photographer then working for AOC, Tim Loveless, did a tremendous job.

The significance of the press as an industrial archaeological artifact was summarised as follows ~

• It was housed within one of the earliest of a new generation of newspaper buildings, the internal design of which influenced those which followed

• the press room at Northcliffe House was the first in Britain to use magazine reel stands. As an example of an early 20th century unit type newspaper printing press, it is an uncommon and possibly rare survival in both the museum and non-museum environment.

• Two other newspaper presses were known to exist in the collections of British museums, but were different in both scale and structure and, in reality, did not represent the sweep of development in the newspaper printing industry. In a wider context, in the European museum environment, the survival of such presses appears likely to be rare.

The above points, together with the planning condition placed upon the press, meant that, in the first instance, attention was focused on the best means of its preservation within the new building. However, the developers were adamant that it would not be possible to allow public access to the press in the new commercial building. Their solution was to enclose the press within a ‘purpose built structure’ thus isolating it from the rest of the new building. I contacted the English Heritage case officer dealing the site and he was not happy about that solution but had to admit that ultimately EH would be powerless to resist it. I then contacted a sympathetic Quantity Surveyor acquaintance of mine who took a pragmatic view and noted that the space occupied by the press would result in a significant loss of rental income. He did a calculation and concluded that such loss of rental income, capitalised over 20 years, would be potentially of the order of some hundreds of thousands of £’s. It occurred to me that an argument might be made that for a lesser sum the press be dismantled by specialist contractors and put into storage pending its reassembly in a suitable new home. The developer was interested in that solution, with its possibilities for attendant good publicity, and EH agreed that such an approach could be considered. Contact was then made with Dr John Griffiths, Science Museum, who was most interested and enthusiastic about the press and the possibility of it being put on display on the Science Museum’s new outstation at Wroughton, Wiltshire.

So, after successful negotiations with Hilstone Corporation for a £250,000 ‘dowry’, it was agreed by them and the Science Museum and English Heritage that arrangements be made with specialist contractors for the dismantling, temporary storage, transportation and reassembly of the Wood printing press at Wroughton, the site of a former WWII RAF airfield.

A considerable achievement and a tribute to lateral thinking and negotiating!

John Maloney