Sir Richard Blackmore was a once well-known but now obscure and forgotten poet, physician, and writer on religious and political matters. Blackmore made a name for himself as a prolific writer but a dull one, whose poetry ‘could put lawyers to sleep.’ Despite his critics, his work was admired by Dr. Samuel Johnson.

Richard, the son of Roberte Blackmore, an attorney at law, was born somewhere to the south of Corsham, probably in Westrop, then known as Westrip, during the Commonwealth. An entry in the Corsham Parish Register shows he was born on 22 January 1654.

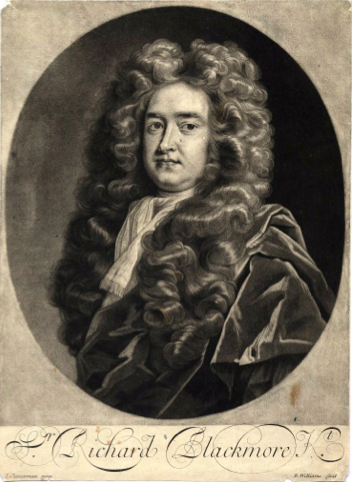

Sir Richard Blackmore Kt

© British Museum

He left Corsham for Westminster School reputedly at the age of 13. He entered St Edmund Hall, Oxford in 1668, took his BA degree on 4 April 1676, and proceeded to MA on 3 June 1676. He resided there for 13 years. His necessities compelled him to temporarily adopt the profession of schoolmaster which was considered an humiliation. With this fact his enemies frequently taunted him in later years:

By nature form’d, by want a pedant made

Blackmore at first set up the whipping trade

Next quack commenced, then fierce with pride he swore That toothache, gripes and corns should be no more:

In vain his drugs as well as birch he tried,

His boys grew blockheads and his patients died.

After abandoning schoolwork, Blackmore spent some time abroad. He visited France, Germany and the Low Countries, and took a Medical Degree at Padua. He returned to England and married Mary Adams in 1685 at St Paul’s, Covent Garden, whose family connections aided him in winning a place in the Royal College of Physicians in 1687. He had trouble with the College, being censured for taking leave without permission and he

strongly opposed the project for setting up a free dispensary for the poor in London. This opposition would be satirised by Sir Samuel Garth in The Dispensary in 1699. His residence was in Saddler’s Hall, Cheapside, and his friends were chiefly in the city. In the early part of Blackmore’s time a citizen was a term of reproach; his place of abode was another topic on which his adversaries took issue, in the absence of any other scandal. He became censor of the College in 1716; and was named an elect on 22 August 1716, which office he resigned on 22 October 1722.

In 1695 he had published ‘Prince Arthur, an Heroick Poem in X Books’, which reached a second edition in 1696, and a third in 1714, an enlarged edition in 12 books also appeared in 1696. So many editions was uncommon at the time, when literary curiosity was restricted to certain classes. The writer tells us that ‘his work was written in such scant moments of leisure as his professional duties afforded’, and for the greatest part, in coffee houses, or in passing up and down the streets. Shortly after its publication, the poem, although some doubted this description, was attacked by one John Dennis in a criticism which Dr Johnson pronounced to be ‘ more tedious and disgusting than the work which he condems’. Far from resenting the attack Blackmore took occasion in a later work to praise Dennis as ‘ equal to Boileau in poetry and superior to him in abilities’.

Having early on declared himself in favour of the revolution, King William, on March 18th 1697, knighted Blackmore, and chose him as one of his physicians extraordinary. On Queen Anne’s accession, he was also appointed one of her physicians, in which office he continued for some time, but his services were dispensed when the Queens’s children all died at an early age.

In 1705, with Anne on the throne and William dead, Blackmore wrote another epic, Eliza: an Epic Poem in Ten Books, on the plot by Rodrigo Lopez, the Portuguese physician, against Queen Elizabeth. Once more, the “epic” was current events, as it meant to denounce John Radcliffe, a Jacobite physician who was out of favour with Anne. Anne did not appear to take sufficient notice of the epic. Two occasional pieces followed: An advice to the poets: a poem occasioned by the wonderful success of her majesty’s arms, under the conduct of the duke of Marlborough in Flanders (1706) and Instructions to Vander Beck (1709). These courted favour with the Duke of Marlborough with some success.

In 1711, Blackmore produced The Nature of Man, a physiological/theological poem on climate and character (with the English climate being the best). This was a tune up for Creation: A Philosophical Poem in 1712, which was praised by John Dennis, Joseph Addison, and, later, Samuel Johnson, for its Miltonic tone. It ran to 16 editions, and of all his epics it was best received.

Blackmore ceased writing epics for a time after Creation. In 1722 he continued his religious themes with Redemption, an epic on the divinity of Jesus Christ designed to oppose and confute the Arians (as he called the Unitarians). The next year, he released another long epic, Alfred. The poem was ostensibly about King Alfred the Great, but like his earlier Arthurian epics, this one was political. It was dedicated to Prince Frederick, the eldest son of King George I, but the poem vanished without causing any comment from court or town.

Blackmore has come down in history, largely through the verse of Alexander Pope, as one avatar of Dulness, but, as a physician, he was quite forward thinking. He agreed with Sir Thomas Sydenham that observation and the physician’s experience should take precedence over any Aristotelian ideals or hypothetical laws. He rejected Galen’s humour theory as well. His papers included:

A Discourse on the Plague, with a prefatory account of Malignant Fevers, 8 vo. Lond. 1720.

A Treatise on the Small Pox, and a Dissertation on the Modern Practice of Inoculation. 8vo. Lond. 1723.

A Treatise on Consumptions and other Distempers belonging to the Breast and Lungs. 8vo. Lond. 1723.

A Treatise on the Spleen and Vapours, or Hypochondriacal and Hysterical Affections; with three Discourses on the Nature and Cure of the Cholic, Melancholy and Palsy. 8vo. Lond. 1725.

A Critical Dissertation on the Spleen. 8vo. Lond. 1725.

Discourses on the Gout, Rheumatism, and King’s Evil. 8vo. Lond. 1726.

Dissertations on a Dropsy, Tympany, the Jaundice, Stone, and Diabetes. 8vo. Lond. 1727.

Blackmore was a poet, not by necessity, but by inclination; and wrote, not for a livelihood, but for fame, or, according to his own declaration “to engage in poetry in the cause of virtue”. But Dryden, Pope, Dennis and some other professed poets of the day treated his performances with much contempt and ridicule. evertheless, Addison and Johnston have bestowed some praise on him; and the latter has, with his usual acuteness and felicity, given a fairly discriminating critique on his writings, which were pretty numerous. Dr Johnson concludes his interesting memoir of Sir Richard, with the following observations:-

“As an author, he may claim honours of magnaminity. The incessant attacks of his enemies, whether serious or merry, are never discovered to have disturbed his quiet, or to have lessened his confidence in himself; they neither awed him to silence or to caution; they neither provoked him to petulance, nor depressed him to complaint. While the distributors of literary fame were endeavouring to depreciate or degrade him, he neither despised or defied them; wrote on, as he had written before, and never turned aside to quiet them by civility or repress them by confutation.”

Blackmore retired in 1722 to live at Boxted. Essex. Dame Mary, his wife, died in 1727 at the age of 68. Richard died two years later, on 9 October 1729 and was buried alongside Mary on 16 October 1729 in the grounds of St Peters Church Boxted, within a few hundred yards of his house, Pond House, which still stands today. The church contains an elegant monument to Blackmore.

It is not thought Blackmore had children; the beneficiaries in his will are mainly nieces and nephews.

Jane Browning