Now that’s a title to get your attention. Let me explain: a newspaper article and a manuscript from St. Patrick’s Catholic Church archive [which was which curated last year by Cath Maloney] shed an interesting –if rather wretched -light on the initial experiences of the Irishmen who came to Corsham during WWII. The Irish Post newspaper article included ‘an edited version of the entry with which Richard O’Gorman won The Irish Post’s feature article competition for Listowel Writers’ Week. The remnant of the newspaper was without a date but must been published post-1945, perhaps sometime into the [early] 1950s ~ I’ve tried finding out online without success.

There follows selective extracts from the article ~

The time 1940, the place Corsham a sleepy little village in the heart of Wiltshire. Britain was embroiled in WWII and a large proportion of her able-bodied were in the armed forces. Meanwhile, the war effort had to be maintained in Britain and in the building and civil engineering industry, that meant some unusual contracts. But there was an acute shortage of labour. In the village of Corsham, a giant underground aircraft complex, occupying a site of some 5 square miles, was awarded to Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners, to whom Sir Alfred McAlpine, George Wimpey and others of such stature were but sub-contractors. The bowels of the Wiltshire countryside had to be blasted and hewed out and brought to the surface by loco-skip trains. To the Irish who worked on the project it was simply called the ‘Corsham Tunnel’.

Men from places like Wigan, Bolton, Northampton and Scunthorpe -many of them veterans of the Mersey tunnel and Pitlochry –all converged on Corsham, the new Klondike of the West Country. All were skilled men at that kind of work, but although they came in droves from all over the country their numbers fell far short of the requirement. In desperation, the contracting companies turned to Ireland for yet more labour. Recruiting offices were set up in many parts of the country and men of all ages and callings were signed up and transported to Corsham. Many were fresh-faced lads who came with all the eagerness of Yukon gold-diggers but their enthusiasm soon confronted reality when they were herded like cattle into the various camps which had been hastily constructed to accommodate them. Soon that area of peaceful Wiltshire became a giant shanty town.

Each hut housed twenty-six to thirty men. Camp beds were positioned close together and, at each end of the hut, there was a coke stove. Other amenities were non-existent. It was primitive in those early days in Corsham. I clearly recall the men using a single stand-pipe in the middle of the camp to wash and shave. Toilet facilities were absolutely crude and the canteens little better than cattle byres. The approach of the camp boss and his ‘hammer gang’ was to take it or leave it.

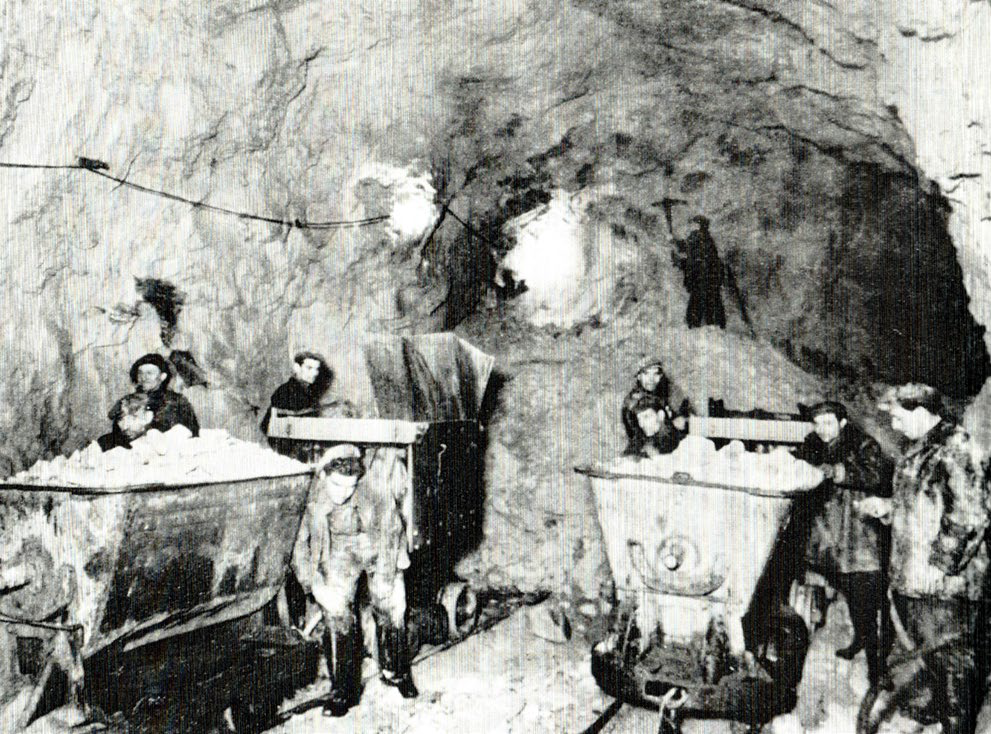

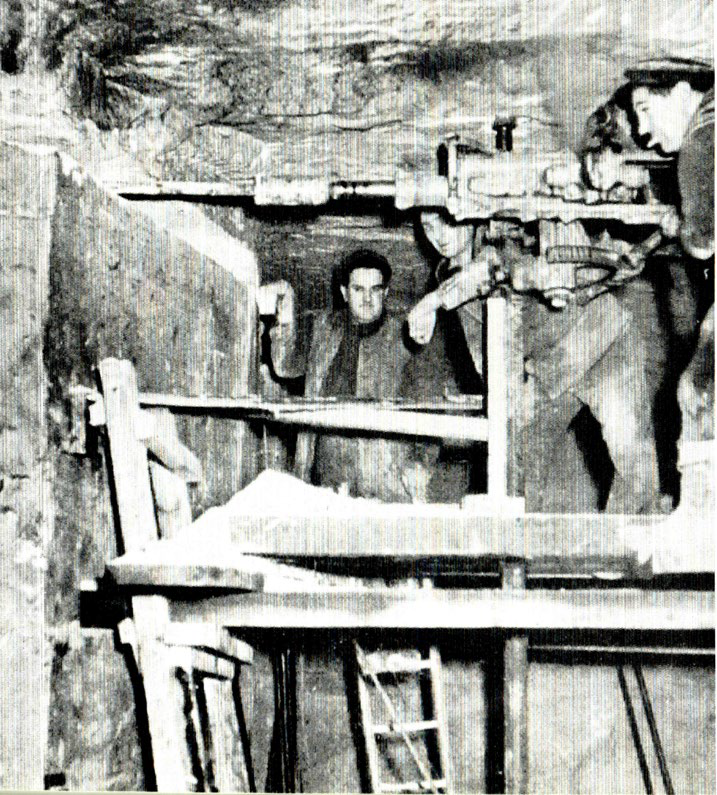

In time, the workers began to organise themselves and to demand their rights. But the early months were soul-searing and only the strongest were able to rise above the indignities. Meanwhile, Corsham was being dug into amidst frenzied activity. Many hundreds of raw Irish youngsters -and some not so young –were literally thrown into the mine to assist the tunnel-diggers, heading drives and blasting gangs. The conditions were awful –the incessant noise of the blasting; the eerie glow of the sodium lamps; the dirt and mud and general debris; and the shrill clanking of the locos with their choking, acrid fumes. They burnt the eyes and made one claw at one’s throat. Even the very spittle in the mouth was as black as the sludge beneath the wheels of those diabolical machines.

Hell could not be worse.

All of the time the work was arduous and extremely dangerous. Every gang was ruled by a hard-faced ganger-man. They worked their charges full cut! McAlpine most often favoured Mayo men in positions of authority: And woe was he who called for the tea, for if you value your life, don’t join by Christ with McAlpine’s ‘Fusiliers’[from a version of the song, McAlpine’s Fusiliers, attributed to MartinHenry from Rooskey, East Mayo, c. 1950]. The ‘tunnel’ steamed on. Much blood was spilt in needless accidents. Dozens, perhaps, ultimately, scores were killed or maimed for life. However, at least conditions in the huts became better as the men began to assert their rights. The contractors noted the changing mood of the men and, in general, acceded to their demands. Temporary churches, recreation halls and even a makeshift cinema sprang up and life above the ground, at least, became more bearable. Furthermore, hundreds of men went into digs in the local towns and the bosses again cooperated by supplying fleets of buses to ferry them to and fro.

All of the time, the general attitude of local people seemed to be one of resentment, bordering on hostility towards the Irish men: at best we were intruders, at worst, army dodgers. Many VIP’s came to view the great excavation, among them Winston Churchill, Ernest Bevin and the gracious Queen Mary. Then came a dramatic event: the great air-raid on Bath when for three hours the Luftwaffe dropped bomb after bomb. Many scores lost their lives and many hundreds were injured that night. Many Irishmen who by then in digs in Bath or who were visiting the town that night were killed. Some were never identified as, generally, the navvies travelled incognito for reasons of their own.

By now the camps were well-organised and a great community spirit prevailed in the huts. The work of dedicated priests contributed much to that. As the months stretched to years, the Corsham ‘Tunnel’ began to take shape and show itself as a masterpiece of civil engineering. In time the momentum began to slow down the great ‘Tunnel’ was almost completed. It had taken three years of toil, sweat and lost lives. Soon we were being dispersed to various other priority jobs all over Britain. Despite everything, there were few of us, as we walked away from Corsham, didn’t feel some twinge of nostalgia. It was a distinct part of Irish life in Britain during those years. We would never again know anything like it. Of all the thousands of Irish workers who passed through Corsham, not one will ever forget it.

Also in the archive is a manuscript entitled ‘My Life’ by Billy McCombwhich recounts experiences similar to that which RO’G wrote about ~ what follows is an extract:

William ‘Billy’ McCombcame to Corsham in 1940 to work for McAlpine’s Constructions stone blasting and skip filling at Spring Quarry (RAF Rudloe), 120ft underground. He along with 40 other labourers lived in wooden huts in a camp with very basic facilities: washing was in a trough using cold water, and toilet facilities were holes in the ground. When he wrote his first letter to his mother in Ireland, his return address was Labour Camp, Thorny Pits, Corsham. His mother responded “For God’s sake, Billy, come home immediately from that dundgeon”. But he stayed, raised a family and for his remaining 58 years was a devoted supporter of St. Patrick’s Church.

This is dedicated to my father, John ‘Jack’ Maloney who came to England from Co. Mayo in 1945 and worked in London on WWII bomb sites clearing rubble and, also, on the building of additional runways at Heathrow Airport during 1948-9 where he first met my mother, Catherine (also from Mayo). Shortly after they were married and whilst working for George Wimpey he was involved in the Harrow Wealdstone train crash during the morning rush hour of 8 October 1952: 112 people were killed and 340 injured and it remains the worst peacetime rail crash in the United Kingdom. Both his legs were amputated just below the knee and right hand just below the elbow. However, after a period in hospital he was fitted for artificial limbs, learnt to drive an adapted car and went back to work with Wimpey running their Transport and Plant in Hayes, West London.